Get rid of carbon

Net-zero biomass burner tanks

Nigel Aylwin-Foster continues his series on the decarbonisation of the school campus by looking at how to develop an effective plan

In the first of this three-part series, beginning in the autumn 2023 edition of Independent School Management, I looked at the purpose of developing an estate decarbonisation plan (EDP), and the relationship between sustainability more broadly (the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals) and net-zero carbon and net-zero energy in schools. In this edition I’ll consider how an EDP is developed.

As a reminder, estate decarbonisation means ceasing to use or rely on fossil fuels for the operation of the school estate across all the estate’s heat, transport and power requirements. The purpose of an EDP is to lay out how a school intends to achieve this. Along the way the EDP will also cover how to reduce the estate energy usage as far as practicable, in itself a decarbonisation measure: however, the school’s main interest in this aspect is likely to be the reduction in operating costs.

Good planning

A well-structured EDP requires careful study of the school estate – the plan is the output from that study. The planning process will require external expert support but some aspects of it will need to be determined by the school staff. Generally, the supporting consultant’s job is to analyse and present the options, including the varying impact of the relevant factors, whereas the supported school will need to decide on its preferred option(s), based partly on the consultant’s input but also on its own input where appropriate. For example, the school will need to determine its relative priorities between the net-zero endeavour and other competing calls on time and funding; and it will need to gauge the available annual budget for decarbonisation. Dialogue between the school and consultant is therefore important during the development of the plan.

Developing an EDP is an iterative process. The optimum overall net-zero engineering solution for the estate needs to be determined, then – working back from that – the plan to get there as efficiently and affordably as possible.

So, how does this work in practice? The EDP study starts with measuring the current energy usage and carbon footprint, as well as understanding the operation and intended future development of the estate, and any other factors that would impinge on the plan – for example the likely trajectory of future energy prices and government policy towards net-zero implementation. This establishes the baseline.

The study then needs to consider:

A – The energy efficiency measures available to reduce energy usage as far as possible and prepare the estate for conversion to low-carbon systems.

B – Options for the independent generation and storage of power on the estate, to reduce the estate’s reliance on grid power, thus also reducing operating costs and increasing estate resilience.

C – Engineering options for the conversion of the heat, transport and power assets at the school to low-carbon systems.

D – The integration and control of all the intended infrastructure changes, such that they work together to optimum effect for the school estate in terms of ease of use, and impact on cost and carbon emissions.

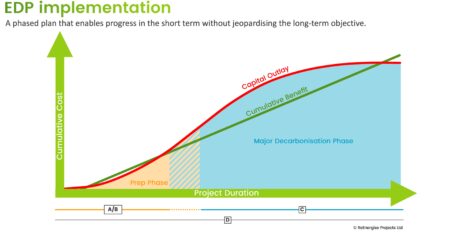

Note that the lettering (A-D) has been included for ease of identification on the EDP implementation diagram shown above; it does not imply a particular order of study in developing the EDP. In practice the EDP study team would need to be considering aspects of serials A to D concurrently. For example, the solution for heat (the defining issue in serial C, above) will depend to some extent on the options available for serials A and B. Conversely, the solution for serial B will depend to some extent on the preferred option for the heating system conversion.

Careful consideration of serials A to D will enable the optimum overall engineering solution to be derived. It is then a matter of working out the most efficient programme to get from the current baseline to the overall engineering solution: this output constitutes the decarbonisation plan.

Given that implementing the decarbonisation plan will entail significant capital outlay at a time when funds are inevitably short, the trick will be to derive a plan that enables progress in the short term without jeopardising the long-term objective. Any short-term projects should be selected based on meeting two criteria: that they will be enablers for the longer-term projects and/or reduce operating costs. The diagram above encapsulates this. It is illustrative of the general idea – of likely trends, and not meant to be to scale.

The Prep Phase is focused on implementing serials A and B, and those elements of serial D that need to be put in place early on. It should normally start as soon as possible, given that there’s nothing to be gained by waiting. These measures should result in some reduction in operating costs, ideally leading to a temporary net benefit. However, the extent to which energy efficiency measures will save a school money is often exaggerated. There’s no doubting that on most school estates operating costs can be reduced through such efficiencies, but they will not prove the panacea that some hope for and they will certainly not prove to be the net-zero silver bullet: sooner or later those fossil fuel systems will have to be removed.

The Major Decarbonisation Phase is focused on implementing serial C and the remaining elements of serial D that cannot be put in place during the Prep Phase. The start and end dates for this phase will depend on a combination of achieving regulatory compliance, the school’s scale of ambition and implementation of net-zero versus other priorities, finding funding and a cost-effective and affordable pathway, and engineering necessity. This phase might, therefore, start once the Prep Phase is complete, or it might overlap to some extent. It will depend on the factors and will vary for each school.

The projects in the Major Decarbonisation Phase are likely to lead to a net loss in terms of cash flow during their implementation, because of the high capex. In due course the net economic effect may well become positive compared to the base case of doing nothing. That rather depends on what happens to relative fuel prices, in particular grid gas versus grid power for any solutions based around conversion of the heating plant to heat pumps, the latter being the most common technology option in schools. The good news is that the UK government has declared its intention to rebalance grid prices to render heat pumps more economically attractive, The challenge will be achieving that in a way considered fair and affordable by consumers. And, of course, reducing a school’s reliance on grid electricity (serial B) will help.

EDP benefits

A well-crafted estate decarbonisation plan enables a school to determine how to achieve the following benefits:

- Operating costs savings and carbon reductions through greater estate energy efficiency.

- Reduced dependence on the national power grid and improved estate resilience, through reduced energy usage and generation of more of the required power on-site.

- Estate decarbonisation (the removal of fossil fuel systems) at whatever pace emerges from the supporting study.

- The avoidance of future costly errors by not stumbling into estate development mistakes that might not have been recognised without the benefit of a comprehensive plan.

The plan also provides budgeting clarity for the short, medium and longer-terms and enables a school to tell all its stakeholders what it is going to do about tackling the hardest aspect of becoming net-zero, based on credible, authentic detail rather than generalisation and wishful-thinking.

Looking ahead

In the next and final article in this series, I’ll bring this process to life by offering insights based on case studies from schools that have already developed their EDPs.

Nigel Aylwin-Foster is the business development director for ReEnergise Projects.

Nigel Aylwin-Foster