People like us

The social profile of governors has changed little over the years and, in changing times, is your governing body doing all it can to reflect the make up of the people it serves? Mike Buchanan digs a little deeper

Most governing bodies of fee-paying schools in the UK are made up of people like me: white, male, 50-plus years old, highly educated, affluent and from a narrow range of backgrounds and professional experiences. A survey covering state-maintained schools by the National Governance Association (NGA) found that 93% of respondents were white and that this proportion has hardly changed over the past 20 years. According to the NGA, just 1% are from mixed or multiple ethnic groups, 3% are Asian, 1% are black, 91% are aged 40-plus and 99% are aged 30-plus.

I don’t think these statistics are collected for independent schools in the UK, but they should be, and I’ve no reason to suppose they would differ in any substantial way. In other words, most schools are largely governed by people like me.

So what? I consider myself to be open-minded, thoughtful and inclusive in the way I behave so, given this, surely the most important thing I bring to the boards I sit on are my skills, knowledge and experiences gained over many years working in and with schools across the world. Surely these characteristics are more important than someone’s background. Diversity is a nice-to-have, but let’s not have the tail wagging the dog. This is exactly the argument I have encountered in 2021 when working with governing bodies.

All change

Many things will automatically change as a result of the pandemic. Some things must be changed post-pandemic and the place of equality, equity, diversity and inclusion (EEDI) as a central feature of our schools should be one of the changes. And it must be led from and by the governing bodies of our schools.

There are many business-led reasons why greater diversity and inclusion are positive steps for schools to take, not least that employees and students in those schools will have a richer experience, contribute more, and achieve more highly as a result. If you need a rational argument for change then this is a good one. Alongside this is the emotional, moral argument. As a governor of a school, would you set out with the intention of making people in your school community feel excluded, unheard, unseen, unsafe, untrusted, unvalued and lacking respect for who they are? In other words, feeling as if they do not belong. I hope the answer is “no”. Nonetheless, this is the reality for some students and their families in our schools.

No more lip service

Diversity and inclusion are not ‘nice-to-haves’. They are the foundation upon which positive, productive and joyous communities are built. For too long we have paid lip service to the idea of their importance and waited in hope that the statistics might naturally evolve over time. This strategy of hope over action has failed too many people in our care: colleagues, students and their families. Some schools have set out deliberately on a different path, often driven by a combination of enlightened head and chair.

A good starting point is for the board members to explore their individual understanding of the terms and come to a shared language. This process takes time and careful exploration; it may be best facilitated by an outsider. I find it ironic that as a white, privileged, older man I am increasingly being asked to talk with boards about diversity and inclusion. I am told that’s because I can provide a degree of psychological safety and, hence, prompt an open conversation. This fear of ‘getting it wrong’ is a powerful driver of hesitancy and inaction. So how might a board start such a conversation?

Get talking

In order to promote productive dialogue, governors might start by exploring:

- How employees, students and parents experience inclusion as well as their own perspectives, and

- Begin to outline a vision for the future based on these findings and their agreed common language. In other words, governors might address:

- Why EEDI matters and to whom.

- The role of governors in leading on EEDI.

- What EEDI mean to the employees, students and parents.

Coming to your own, visceral definition of the terms is a crucial step in bringing good intentions to life in your school. These are the litmus tests of future success. Recently, a board I worked with came up with this agreed understanding:

- Equality = treating people as equals over and above statutory requirements.

- Equity = recognising different starting points and removing their impact by positive actions.

- Diversity = recognising all the differences that any group of people represent and the benefits of these differences.

- Inclusion = an emotional response to feeling respected, valued, safe, trusted and having a sense of belonging.

The board also agreed that ensuring that all parts of the school community (students, employees, families, governors and supporters) should feel included and that this goal should drive the activity of the school from the board downwards.

New goals

In order to achieve this intention, the board set out the ambitious goals below and now plan, with the school leaders, to co-create and support the steps required to make rapid progress towards these goals:

- There should be no gap in attainment between students which arises only from their background.

- Students, employees, families and governors should feel included.

- The curriculum should be inclusive as reflected in the two bullet points above.

- Adults should report confidence in their ability to manage EEDI without fear.

- Students and employees should feel safe and safeguarded when reporting on their degree of inclusion.

- Students and employees should report a sense of fairness in access to and allocation of opportunities.

Be practical

There are many practical steps that follow from such a statement of intent, from challenging mindsets and tackling systemic biases, to agreeing measures of progress. Proper investment of time and other resources is also needed. Crucially, where schools are being successful it is because they have ensured that their approach is part of their culture. Where schools have not yet had success it is typically because EEDI is seen as an add-on, is tokenistic and formulaic.

Importantly, governors should be seen to be intentionally leading and not merely supporting steps towards greater inclusion and diversity as shown by who is on the board. However difficult, this means actively seeking to ensure the board has a mix of genders, ethnic, social, educational and professional backgrounds, as well as other protected characteristics, and a wide, balanced range of ages so that the phrase ‘people like us’ becomes a positive affirmation of inclusive practice rather than an accusation of exclusion.

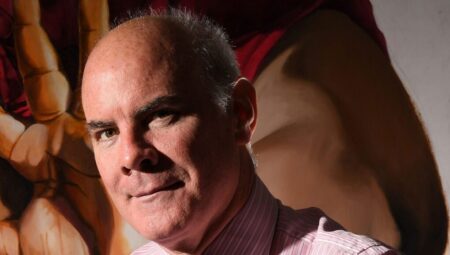

Mike Buchanan is the founder of PositivelyLeading and was formerly the executive director of HMC.

Mike Buchanan

©Russell Sach