Why net zero?

In the first of a series of three features, Nigel Aylwin-Foster outlines how to plan the decarbonisation of your school estate

Five years ago, I doubt the term ‘EDP’ had ever have been heard of in the independent education sector: it stands for ‘Estate Decarbonisation Plan’. Now, with the marked increase in focus on becoming net zero within the UK, not least in the education sector, the EDP has become an important planning tool for schools. Every school will need one, and staff must understand what it is and why it matters. It’s not a long-shot to suggest that within the next five years every school in the sector will have developed one, even if the school doesn’t intend to implement the plan for several more years. After all, even if the intent is to leave an action until the last safe moment, without a plan, how does one know what the last safe moment is?

This article will explain the Why? and the What? The two subsequent articles will look at the How? in more detail.

THE PURPOSE OF AN EDP

Being net zero carbon means ceasing to use or rely on fossil fuels for any part of the school operation, including in the supply chain and off the estate (for example, staff commuting and school trips on commercial transport), or

offsetting where the irreducible minimum of fossil fuel usage has been reached.

Estate decarbonisation therefore means ceasing to use or rely on fossil fuels for the operation of the school estate – in essence, for all the estate’s heat, transport and power requirements. Notwithstanding the challenges, all schools in the UK should eventually be able to achieve this, although it will take time, money, effort and appropriate prioritisation.

The purpose of an EDP is to describe how a school intends to achieve this. This needs to be worked out in enough detail to determine a programme for implementation, along with the management, resourcing and budgeting requirements. The latter is important, so that the school can invest accordingly to its broader development plans.

In most cases, the resulting programme of decarbonisation will last at least a decade, probably two. The EDP will inevitably require some adjustment en route to the school achieving net zero carbon, but that does not negate the worth of drawing one up in the first place.

WHAT’S IN AN EDP?

Developing an EDP is the work of some months of study, culminating in the production of the plan. Undertaken with the necessary engineering and commercial rigour – and with a keen eye on pragmatism and practicality in an educational setting – the task is akin to crafting an estate master plan, except that the subject matter is mechanical and electrical rather than an exercise in managing the time frames for when to build.

A well-crafted EDP will:

• Take account of the school’s current situation and general development plans, both in the physical and broader educational sense • Provide an update on the political, legislative and commercial context of the work. These all have some bearing on the decarbonisation options

• Provide a clear description of the opportunities, costs, timescales and impact of the full range of decarbonisation work required on the estate, with supporting technical, engineering, and commercial logic. This includes the scope for improving energy efficiency on the estate, so that less energy is required in the first place, as well as the scope for the conversion of the estate’s energy systems to alternative low-carbon technologies

• Provide preliminary scopes of work and design concepts for the more complex infrastructure projects, largely driven by conversion of the heating plant and the changes to the power infrastructure required to support the heating plant conversion. (Note that conversion of the heating plant will almost always be the most challenging and expensive project within the plan. Even though, in some cases, it could be a decade or more before the fossil fuel heating plant needs to be phased out, it’s not feasible to estimate the conversion costs realistically without drawing up at least a preliminary design concept. This matters, because the costs are such that they are almost bound to require some significant changes to the school’s existing development plans: it’s in a school’s interests to understand the potential impact sooner rather than later)

• Take account of the interactions between the various technologies involved, to produce an integrated design concept for the use and development of heat, transport and power systems across the estate.

• Produce a cost/benefit analysis for each major project enshrined in the plan, including an estimate of the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and potential reduction in operating costs

• Provide metrics to measure year-on-year progress, with reductions in energy usage and carbon emissions

• Set out a year-by-year implementation programme for all the major energy efficiency and decarbonisation projects, including annual estimates for the required capital outlay. The work can then be incorporated into the broader estate development plan, so that funds can be raised and allocated in a timely fashion and projects can be executed in good order when required, rather than being rushed. Low-carbon conversion projects in schools do not respond well to being rushed, especially the core business of converting the school’s heating.

• Advise on the immediate next steps required to start turning the EDP into action.

THE EDP IN CONTEXT

The terms ‘sustainability’ and ‘net zero’ often seem to be used interchangeably, but in practice they are not synonymous and it’s worth being clear about the interrelationship. Both will come to matter more and more in schools, and resources need to be targeted with a clear sense of purpose.

Environmental sustainability encompasses everything from reducing emissions to encouraging biodiversity, reducing the extinction of species and even investing sustainably. The most commonly used agenda for this in the independent education sector is the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals shown below:

We’ve already discussed the purpose of net zero carbon, but there’s now another net zero on the block – net zero for energy.

Being net zero for energy means a school generates as much energy as it uses, even though it may still need to buy energy from external sources. This is not the same as being net zero carbon – a school could in due course become net zero carbon but still be heavily reliant on the procurement of energy from external sources. In contrast, a school could be net zero for energy but still not be net zero carbon. The distinction between the two is somewhat nuanced but it’s important to be clear about the school’s priorities before an EDP is developed because it will influence the development of the plan. Net zero carbon is ultimately about reducing the impact of climate change; net zero for energy is motivated by the desire to reduce operating costs.

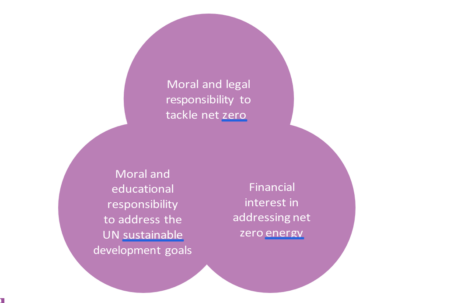

The Venn diagram below illustrates the interrelationship between these three purposes, within a school context:

As already outlined, all schools in the UK should be able to achieve net zero carbon (given time, money and effort) whereas most schools in the UK will not be able to achieve net zero for energy, simply because they lack the real estate to be able to install the required onsite power generation and storage systems. However, they will still be able to get part of the way and it will remain a worthwhile goal.

In my two next two features I’ll outline how to plan for these respective net zero goals.

Nigel Aylwin-Foster is the business development director for decarbonisation specialist ReEnergise Projects.